Kellogg Community College’s main campus displays a quote by W.K. Kellogg that reads, “Education is the only way to really improve one generation over another.”

It’s a great quote and an absolute truth.

I think about that quote from time to time here as I consider what life in my village will be like 5, 10, 20 years from now.

As a volunteer I’m supposed to educate, but I work mainly with adults, people out of school. Some volunteers work primarily with children through different clubs and even by teaching in classrooms, but that’s not for me. Kids are too high-energy, I’d rather play games with them than teach, and I’m deathly afraid of saying something that they’ll listen too closely to and it’ll mess them up for the rest of their lives; like saying “What’s up?” instead of “How are you?” Last year a couple of boys nearly failed their English exams for writing that as an answer. These are the same reasons I switched midway through college from an education major to an environmental sciences focus — because you can’t give a tree a complex for years to come.

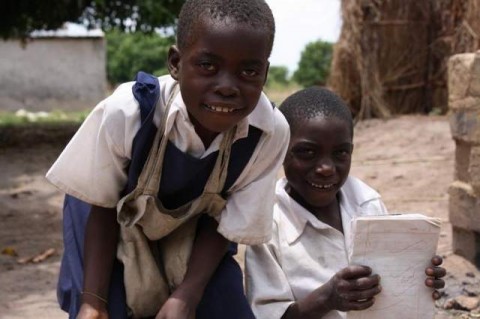

For all my lackluster involvement in the education of Zambia’s children, the government has the Department of Education to teach these kids, or “pupils” as they’re usually called. Providing education from first grade to twelfth grade, children can study a wide array of subjects: biology, religious education, social studies, English, math, cultural studies, and chemistry among others.

But things weren’t always so bureaucratic and regulated. The grandmother in my village said that when she was a little girl there were no schools for any of the children. You learned only what your friends and family taught you.

It began to improve for her son, my village’s headman, when schools were offered. However, to go to school you had to register due to the local chief’s decree. But because it was new, on the day that the education men came around to register the boys, his aunt hid him in the forest fearing that he was going to be taken away and forced to fight in a war. Eventually he went to school and made it as far as 7th grade.

Then there’s my good friend Mr. Nshimbi who said he remembers a time when they were trying to decide which grade older children should enroll into by having the children reach over their heads and touch their opposite ear. If they could touch their ear than they were placed into a higher grade. This was done because no one knew their age; no one knew their birthday.

Unfortunately, most children in my community don’t finish school. Due to a lack of funding or no pressure from parents at home to continue their education, the children don’t finish. Of my headman’s nine children only one has finished all of the way through grade 12 — his daughter Virginia.

At times, it seems like getting an education can be a testament to one’s endurance as some children walk well over two miles one way to get to school, and once there the classrooms are packed with children — sometimes as high as 90 students to one teacher. The gender makeup is often male-heavy because girls tend to drop out sooner to help with chores at home.

Should a child finish school and have the financial means to continue through to college Zambia offers a lot of options in the forms of technical colleges, private universities, and public universities: the largest two being the University of Zambia and Cobberbelt University. Online universities (mostly based in Europe and the United States) are becoming very popular with those wanting to pursue a graduate degree. But, as mentioned, most don’t make it to the university level, or finish through the 12th grade for that matter.

Zambia’s education system has come a long way since independence in 1964 and having children reach over their heads to try and touch the opposite ear, but it’s still slowed due to large class sizes, a lack of resources, overworked teachers, and, most importantly, a lack of emphasis from parents at home to instill the importance of education in a child’s life.

Jordan Blekking of Pennfield is in Zambia as a member of the Peace Corps. His dispatches are reviewed by the Peace Corps before they’re sent.

Visit his blog, jordanblekking.blogspot.com

JOIN DRIVERN TAXI AS PARTNER DRIVER TODAY!

JOIN DRIVERN TAXI AS PARTNER DRIVER TODAY!

Why users still use to read news papers when in this technological globe everything is available on net?